Crisis of Trust 2026: The Retreat Into Insularity

70% are hesitant to trust “the other side.” The 2026 Edelman Trust Barometer offers “trust brokering” tactics—but no clear path back to a shared reality.

Today, Edelman launched its 2026 Trust Barometer, a survey that examines attitudes about trust across 28 countries and 33,000 respondents. I read it every year when it comes out to see what the topline framing is, since the overall trend—declining trust in institutions, government, media, and virtually everything—is by now somewhat predictable. Over the last 26 years of chronicling the erosion of shared reality, Barometers have focused on topics like “Fall of the Celebrity CEO” (2002), “The Battle for Truth” (2018), and “Trust and the Crisis of Grievance” (2025).

This year’s theme is “Trust Amid Insularity.”

The takeaway headline number this year: 70% of respondents globally say they are hesitant or unwilling to trust someone who differs from them in values, information sources, or worldview.

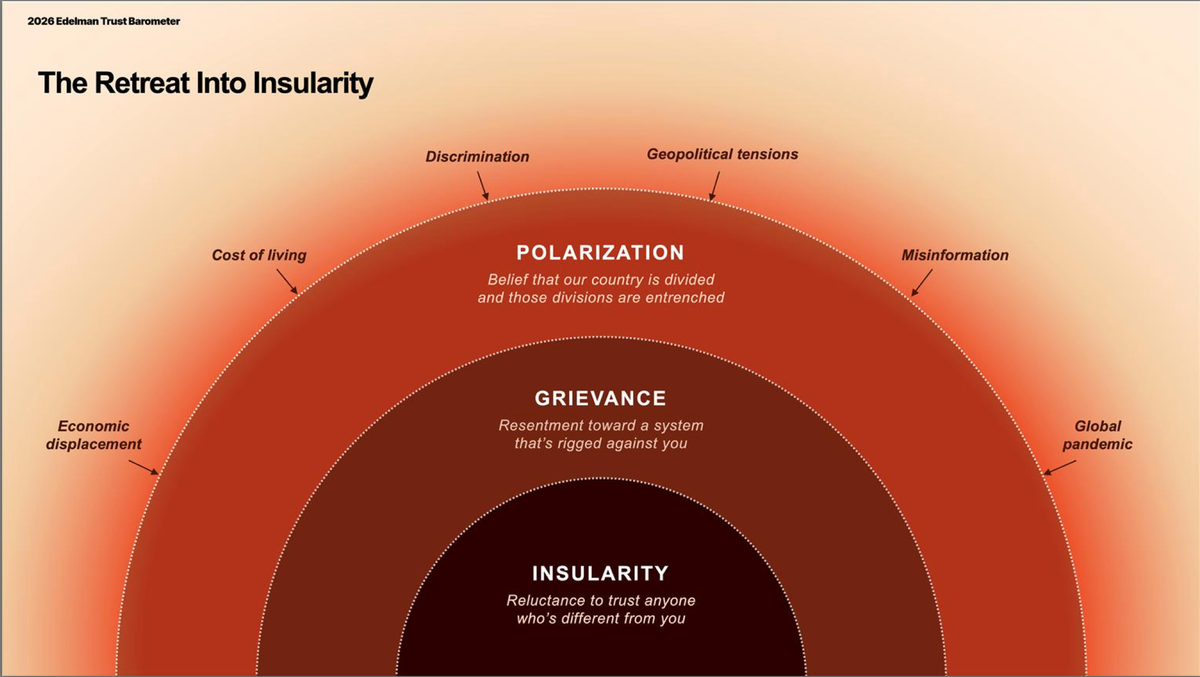

We’ve stopped trying to understand “the other side,” not just politically but epistemically, the report argues. Edelman connects this reluctance to two factors: polarization and grievance. They define polarization as “belief that our country is divided and those divisions are entrenched” and grievance as “resentment toward a system that’s rigged against you.”

What do they think might help us get out of this insularity rut? Influencers.

Since I wrote a book about our ability to construct immersive, insular bespoke realities, I appreciate further official corroboration that we’re in a crisis of trust and increasingly operating with completely different sets of facts. 😉 But I want to highlight a couple of things from the report—and also go a little bit deeper on the influencer thing.

“Trust brokering,” as Edelman calls it, is the idea that since institutions can no longer reach a mass public directly, they should work through intermediaries who already have trust within specific communities: employers, influencers, local leaders. Meet people where they are. Translate between groups. Rather than trying to change people, surface mutual interests and needs.

It’s not bad advice for navigating the current information landscape. But it’s advice for adapting to the jungle, not restoring the commons. And that distinction matters.

The turn inward is measurable—not theoretical

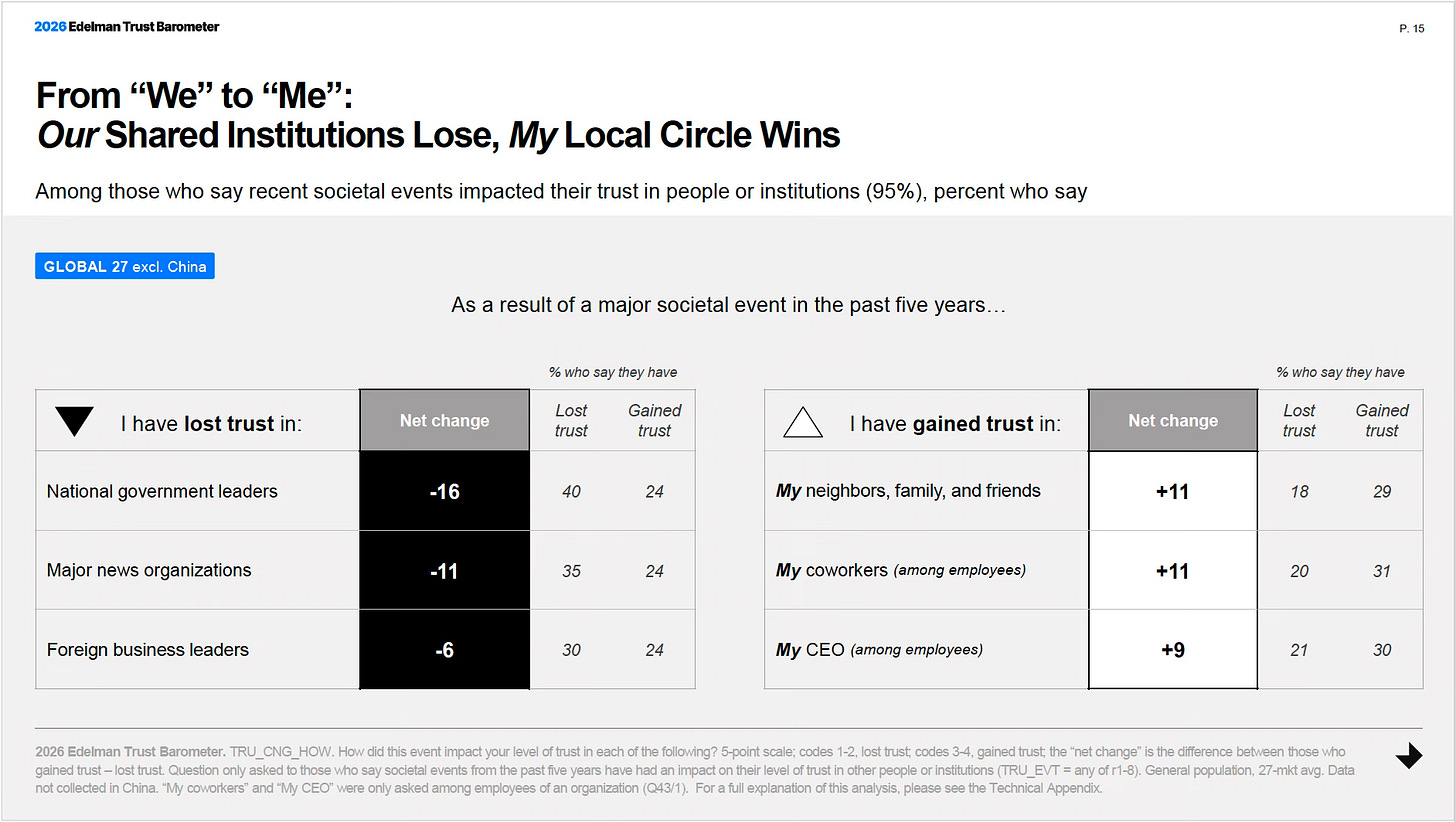

One of the most telling of Edelman’s slides is titled “From ‘We’ to ‘Me.’” People who say that recent societal eventsimpacted their trust patterns—which is nearly everyone in their sample—report an increase in trust for “my neighbors, family, and friends” (+11 net) and “my coworkers” (+11 net), and a decline for national government leaders (-16 net) and major news organizations (-11 net). People even like their CEOs.

This is consistent with the arc Edelman has been charting for decades. “Trust Shifts from Authorities to Peers” was their 2005 theme. (I pulled up the 2005 report, which predates the mainstreaming of “social media” and “influencers”. In one poll about who the most credible corporate spokespersons might be, people in the US ranked doctors and academics at 60%, and entertainers and athletes at 4%.)

What’s new is the depth of the epistemic split: people are now expressing skepticism of anyone who “believes different facts and trusts different sources.” This is happening alongside a decline in exposure to cross-cutting information: the 2026 Trust Barometer notes that only 39% say they get information from sources with a different political leaning at least weekly—down 6 points year-over-year, with significant decreases in 20 of 28 countries. If democracy is predicated on a “marketplace of ideas,” where cross-cutting exposure nudges people to refine arguments or update beliefs, that marketplace is emptying out.

The Infrastructure of Insularity

But to understand why this is happening—and why it won’t easily reverse—you have to look at the media ecosystem itself, which is a bit outside the scope of Edelman’s work. So I want to pull in another report to connect some dots.

The Reuters Institute’s 2025 Digital News Report, released last June, is essentially a field guide to the information environment of our insular world. It’s also a survey, featuring detailed information on the media environments in dozens of countries spanning the globe, with all sorts of analytics on what platforms people are using, media consumption habits, trust in media, etc.

According to the Reuters report, 40% of people now say they sometimes or often avoid the news. Those who do engage are increasingly getting news from social media, especially via video, where mainstream media is losing the competition for attention and distribution to niche creators. A majority (58%) also report feeling like it’s difficult to tell real from fake news online – AI is making this exponentially harder, as even video becomes untrustworthy.

There is a very revealing statistic buried within the Reuters report: when people are asked how they would verify news they weren’t sure about, 38% say they would go to “a news source I trust.” In a follow-up question, United States respondents list their preferred sources: CNN, Fox News, and BBC are the top three. One of these frequently espouses a reality that is fundamentally incompatible with the others. It’s important to understand that ‘checking a trusted source’ doesn’t mean checking against a shared standard—it means checking with your team.

Under-35s, meanwhile, are significantly more likely to verify information via social media comments, AI chatbots, or a quick search (which increasingly returns AI synthesis). Verification involves consulting the feed—which, of course, is often personalized according to your preferences. What counts as “true” is increasingly shaped by context and identity, not vetting.

Edelman’s Trust Barometer describes a condition: insular societies where people increasingly trust only their own side. Reuters explains the fragmented information infrastructure that reinforces and rewards that insularity, where creator commentary outcompetes institutional journalism and verification has become tribal. Together they show a system optimized for division and consensus collapse.

Edelman’s solution treats the problem as permanent

Given this state of affairs, what’s an institution supposed to do? Edelman’s answer is “trust brokering”—work through intermediaries who already have trust within specific communities. If people are mostly verifying within their tribes, reach them through voices those tribes already trust.

The last third of the Trust Barometer report offers an approach for this—the suggestions are more sophisticated than my tongue-in-cheek reduction to “use influencers!” but not by much. We’ve gone from 4% saying a celebrity is a credible spokesperson for a company in the 2005 Trust Barometer to this in 2026: “Among people who trust a food or lifestyle influencer (48%), 62% say they would trust or consider trusting a company they currently distrust if that influencer vouched for it.” For financial influencers, it’s 57% among the 44% who trust one. Trust, in other words, is transferable through parasocial relationships—regardless of whether the institution has done anything to earn it.

It’s worth pointing out that the “among 44% who trust one” caveat is doing important work—because Reuters found that online influencers tied with politicians as the top perceived misinformation threat globally (47% each; celebrities scored lower!). That’s the paradox: influencers are simultaneously the most effective trust brokers and the most distrusted sources. The label covers a lot of different species: from the Besties that do makeup how-tos on TikTok to the Gurus who tell you about the secret health benefits of juice cleanses to the Reflexive Contrarian malcontents who turn political grievance into profit. Different genres, same engine: trust earned through charisma, resonance, and the steady performance of alignment, inside a media ecology built for niches.

Edelman’s playbook includes other recommendations for bridging across insular divides. Employers should “build teams requiring people with different values to collaborate”. CEOs: “consult people with different backgrounds before major decisions”. NGOs: “help distrusting groups understand each other.” Government: “avoid rhetoric that blames or vilifies particular groups.” (Must be for the non-US audience.)

It offers some rather staid advice for media: “provide equal coverage of different viewpoints,” and “write accurate headlines rather than fear-inducing ones.” The problem is that in the jungle, competition practically necessitates clickbait. The algorithm demands it—every news creator on YouTube has to play the headline and thumbnail game. Furthermore, influencers are often successful because they are not providing equal coverage—they’re eating traditional media’s lunch because they’re catering to a niche, particularly in the political realm.

There’s also an elephant in the room with Edelman’s “high trust”-ranking countries: several of the countries at the top—China, the UAE, Saudi Arabia—operate in fundamentally different information conditions than the countries at the bottom. Some of their high reported trust levels may reflect preference falsification when surveyed. But there’s also the simple fact of information control: a tightly managed environment doesn’t just suppress criticism of leaders, it suppresses the kind of constant, identity-targeted conflict that drives polarization and grievance. If the public rarely sees open coverage of leaders’ failures—or doesn’t see elites model “anything goes” divisiveness—trust is easier to maintain, at least on paper.

Ironically, several of the high-scoring countries have recently begun to rein in their influencer spheres, too: China now requires wellness influencers making health claims to have credentials. Saudi Arabia issued new influencer guidelines in September on compensation disclosure, morals, misinformation, etc.

Western democracies, by contrast, with our open speech and open systems, are supposed to have a commons, a marketplace of ideas that allows for cross-cutting dialogue and eventual consensus. It has been replaced by an information ecology shaped by algorithmic selection. Content and creators optimized for engagement outcompete everything else—not because they’re accurate or trustworthy, but because they’re fit.

The question isn’t whether institutions should learn to compete in the ecosystem we have. They have to. And Edelman’s advice in this latest Trust Barometer helps them do that, which is valuable; it may help bolster trust in institutions that were seen as aloof or absent. “Trust brokering” is a useful mechanism for thinking about how to help messages travel through intermediaries, through community validators, through people who already have attention and affinity.

But if we want to repair shared reality and change the direction of the trust trend at some point—if we want a commons again—the incentives of the communication ecosystem are going to have to change. As long as platforms and politics reward outrage over accuracy and identity over evidence, insularity won’t fade. It will only compound.