From Epstein to Everything

The Epstein files are real. The conspiracy theories they're re-fueling aren't. Here's why Pizzagate and Wayfair are surging once again, and why Cenk Uyghur went 9/11 truther.

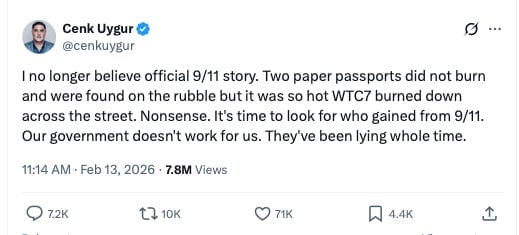

On February 13, Cenk Uygur—founder of The Young Turks and progressive media and political fixture—posted to his 800,000 followers: “I no longer believe official 9/11 story.” The post has 7.8 million views and counting.

Cenk wasn’t the only media elite to have a conspiratorial revelation recently. Two weeks earlier, Cenk had sat down with Tucker Carlson to discuss “Epstein, JFK, 9-11, Israel’s Terrorism and the Consequences of Opposing It.” On the same day the episode was released, the Department of Justice dropped over 3 million pages of Epstein-related documents. Tucker released another episode of his show with conspiracy influencer Ian Carroll declaring that “It looks like Pizzagate is basically real.” Wayfair trafficking rumors suddenly popped up again-–not just among QAnon adherents, from whence they’d emerged in 2020, but among a broad spectrum of people (including left-leaning posters on Threads).

Pizzagate, Wayfair, 9/11 truth mixed up with Satanic panic, deep state cover-ups, vaccine plots, JFK Jr’s return—these claims used to travel together under QAnon’s banner, all wired into one grand everything-is-connected narrative by a shadowy central figure issuing drops. Today, the omniconspiracy is off and running without the Q branding and without the stigma. Nobody’s orchestrating it. It’s pulling in audiences on the right and the left. So it’s worth understanding why some of these conspiracy theories are re-emerging, and how the rhetoric in a declaration like Cenk’s works.

A Scandal as Raw Material

On January 30, the Department of Justice released over 3 million pages of Epstein-related documents—emails, videos, images, financial records—in response to the Epstein Files Transparency Act. The dump was massive, poorly organized, and riddled with both redactions and redaction failures. It was, in other words, the perfect raw material for online sleuths and conspiracy entrepreneurs alike: a vast, chaotic trove of real horror, released without context, into an attention economy that rewards big reveals. People went shopping for receipts to fit their longstanding theories. Sometimes literally: screenshots of a Wayfair purchase receipt began circulating. They searched for familiar brands and familiar keywords (pizza!), clipped suggestive fragments, and presented them to their audiences as vindication of past theories: this is what we meant all along.

The theories that resurface aren’t random—they’re the ones that already had audiences and narrative hooks in place, waiting for new “evidence.” Wayfair and Pizzagate are both elaborate theories about elite child exploitation, so a massive document dump about an actual convicted child sex trafficker was always going to serve as new proof for people who were open to being convinced. The new details don’t have to add up—they just have to feel damning. Sensational interpretations spread while debunkings that highlight the actual facts get dismissed as “cover-ups” or “excuses”, and one real egregious institutional failure becomes permission to doubt everything.

In 2020, the Wayfair conspiracy theory began when a QAnon influencer alleged that the online furniture retailer was trafficking children through purportedly suspicious overpriced product listings whose names matched those of missing kids. The theory was thoroughly debunked at the time; some of the supposedly missing kids (some of whom had been runaways) even made videos asking the sleuths to please leave them alone. Now, in 2026, a viral post showing an authentic receipt from the files was being hailed as allegedly proving the whole thing: one of Epstein’s associates had purchased items totaling $8,453. The post framed this as “a single, unlabeled” item—mysterious, inexplicable, damning. The actual documents, which journalists painstakingly reconstructed from adjacent emails in the files drop, show it was 25 separate products—bathroom decor, furniture, and 14 outdoor light fixtures—shipped to Epstein’s island to furnish a house. But this literal receipt isn’t being used as evidence in the traditional sense, as in, material that helps work toward a conclusion. It’s an artifact that someone can hold up and say, explain this—and then the burden of proof shifts to the person who says it’s just light fixtures. The conspiracy theory is hitting new audiences in the context of an actual scandal. Compounding this, the existing true believers are unlikely to trust the media doing the debunking.

Pizzagate, which falsely alleged that Democrats were running a child trafficking ring out of a Washington, D.C. pizzeria,predated QAnon. It was considered incredibly fringe and kooky when it first emerged, but was gradually incorporated into the Q mythology. Since the Epstein document release, approximately 910,000 posts on X have mentioned Pizzagate, nearly three times the volume of the entire six months prior. The word “pizza” appears in roughly 900 of the 3 million Epstein documents, and people immediately seized on this as proof that “pizza” was always a coded reference to child sex trafficking.

But journalists who have read through all of the pizza references in the Epstein files make the very compelling case that they are actually pretty mundane: people are discussing Manhattan pizzerias, Williams Sonoma pizza stones, youth soccer pizza parties. One email that went viral featured the subject line “U9 Red pizza party”—which conspiracy posters claimed meant the blood of children under 9. It referenced a kids’ soccer team. Meanwhile, Comet Ping Pong, the D.C. restaurant at the center of the original theory appears in exactly two documents—a PDF of an old Atlantic article about the conspiracy itself, and an anonymous FBI tip from 2020. John Podesta, whose emails were the fodder for the original theory (pushed by Jack Posobiec, now himself an elite influencer), appears in passing in only one.

The entire premise of Pizzagate is that elites use coded language to conceal their crimes. Were they? Maybe, though “pizza” sure seems like stretch. In reality, what’s striking about the files is that Epstein and his associates were very openly referring to young girls as young girls in his emails. One compared a girl to Lolita. Peter Attia, longevity influencer, joked about ‘low-carb pussy.’ Donald Trump drew him a birthday picture shaped like a young naked woman. Epstein himself wrote, to a redacted person, “Your littlest girl was a little naughty.” The Epstein class didn’t need code words. They had impunity.

Ok but why, you might be wondering, is 9/11 trutherism back?

Let’s get back to Cenk.

Moments of real institutional failure don’t just produce anger—they often produce free-floating suspicion: What else have they been lying about? The Epstein files offer incontrovertible evidence that powerful people are protected, that accountability is optional for elites. In 2020, that suspicion often came packaged as QAnon, which had child exploitation as the moral anchor but took people on a journey into a broad story of institutional deceit where every scandal was proof of the next. Research on conspiracy belief is pretty consistent that people who buy into one conspiracy are more likely to buy into others—even contradictory ones—because the underlying belief is that someone is hiding the truth.

9/11 trutherism is a readily-available conspiracy theory with that same premise. It comes with several “explain this” moments, and for Cenk it perhaps neatly intersects with some personal beliefs about US imperialism and Israel. But what makes Cenk’s posts interesting is that they’re a conversion announcement, in public, from a fairly high-status figure on the left. So let’s dissect his thread itself.

Cenk’s Great Awakening

Cenk’s thread is a tight case study in how conspiracy thinking travels now: not as a coherent alternative account of a situation, but as rhetoric that turns distrust and nihilism into the “reasonable” stance. It’s conspiracy without the theory.

He starts with a confession: “I no longer believe…” This is a high-status account publicly declaring a change in position, a courageous awakening. He’s broken free and is inviting followers to update their beliefs alongside him. I used to be like you. I was asleep. Now I’m not. Come with me. (Tucker using “I was wrong” about his change of heart on Pizzagate has the same rhetorical effect.)

Then Cenk drops an “evidence collage” featuring two anomalies—paper passports surviving the crash, WTC7 collapsing. This is fairly flimsy stuff! It’s not actually offering an alternative explanation for 9/11. It’s just “How could this be?”-type questions, the physics of which are extensively discussed in many places. But he declares that these facts are incompatible with the “official story”...

And then quickly pivots to insinuation: “It’s time to look for who gained from 9/11.” Once you’re in cui bono territory, you can speculate forever. This is a classic conspiracy theorist rhetorical move because it’s unfalsifiable; there’s no claim to disprove. Someone should really look into this. What? What they’re hiding from you.

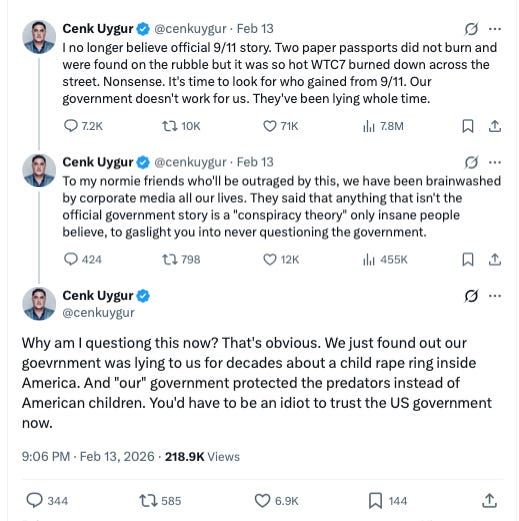

Finally, there’s the preemptive delegitimization of rebuttal: “To my normie friends who’ll be outraged by this, we have been brainwashed by corporate media all our lives.” This preemptively turns criticism into evidence that the critic is captured. The more people push back against Cenk, the more it proves the conspiracy is real. He reframes the term “conspiracy theory” similarly: it’s not a category of narrative built on bad inference, it’s a smear imposed to keep us from questioning power. The net effect is to make the audience feel powerful for rejecting the very idea of being corrected.

“Why am I questioning this now?” he asks in closing. Cenk’s conversion to 9/11 truther isn’t based on any information actually related to 9/11—it’s the transitive effect of Epstein. “You’d have to be an idiot to trust the US government now.”

Why This Matters

It’s not clear whether conspiracy theory beliefs are actually more prevalent today than they’ve been in the past; polling research has suggested that prevalence is largely holding steady, but the theories are becoming more visible. They certainly seem to be more normalized among new media elites, which is itself a phenomenon. When Cenk Uygur, a trusted elite media figure with millions of viewers across his channels, announces “I no longer believe the official 9/11 story,” it doesn’t just state his belief, it potentially shifts that belief’s acceptability. It tells followers that this isn’t embarrassing—it’s brave. It signals to adjacent creators that the belief is no longer a marker of crankery. Tucker’s “Pizzagate is basically real” commentary is doing the same thing. Once high-status people endorse a theory, the thinness of the evidence matters less because reputation supplies the credibility that the argument lacks.

Derek Thompson wrote after quote-tweeting Cenk, “I worry that the social penalty of announcing that you believe in nonsense is going down.” It absolutely is. For a lot of big influencers, professing belief in what brainwashed mainstream institutionalists call “conspiracy theories” has become a reliable way to signal independence, attract attention, and harvest engagement. There’s no reputational cost at all; quite the contrary. You can rack up Substack subs as a delusional nutjob and earn a very nice living.

Meanwhile, pushing back has gotten harder. When the Wayfair conspiracy went viral in 2020, social media platforms and journalists worked to debunk it because the harms to the kids and employees named were obvious. In 2026, some companies are afraid of being accused of “censorship” for factchecking; others saw an opportunity to reduce costs while kowtowing to the administration. So the claims are simply spreading to new audiences as recommendation engines curate posts into people’s feeds. Community Notes, which I like and support, is just not keeping up, particularly on Meta properties. This isn’t great. Widespread belief in baseless theories like Wayfair or Pizzagate is corrosive. QAnon was essentially a cult; people seem to have forgotten the stories of family members becoming unrecognizable.

Meanwhile, the Epstein files contain genuinely damning material suggesting decades of elite impunity, institutional failure, and the abuse of vulnerable young women. That’s real, and it matters. Going down some 9/11 rabbit hole takes the legitimate rage the Epstein case should produce and converts it into tangential content. Conspiracizing builds audiences, not coalitions for accountability. And it leaves the public conversation stuck on whether “pizza” is a code word rather than on why so few people have been prosecuted.