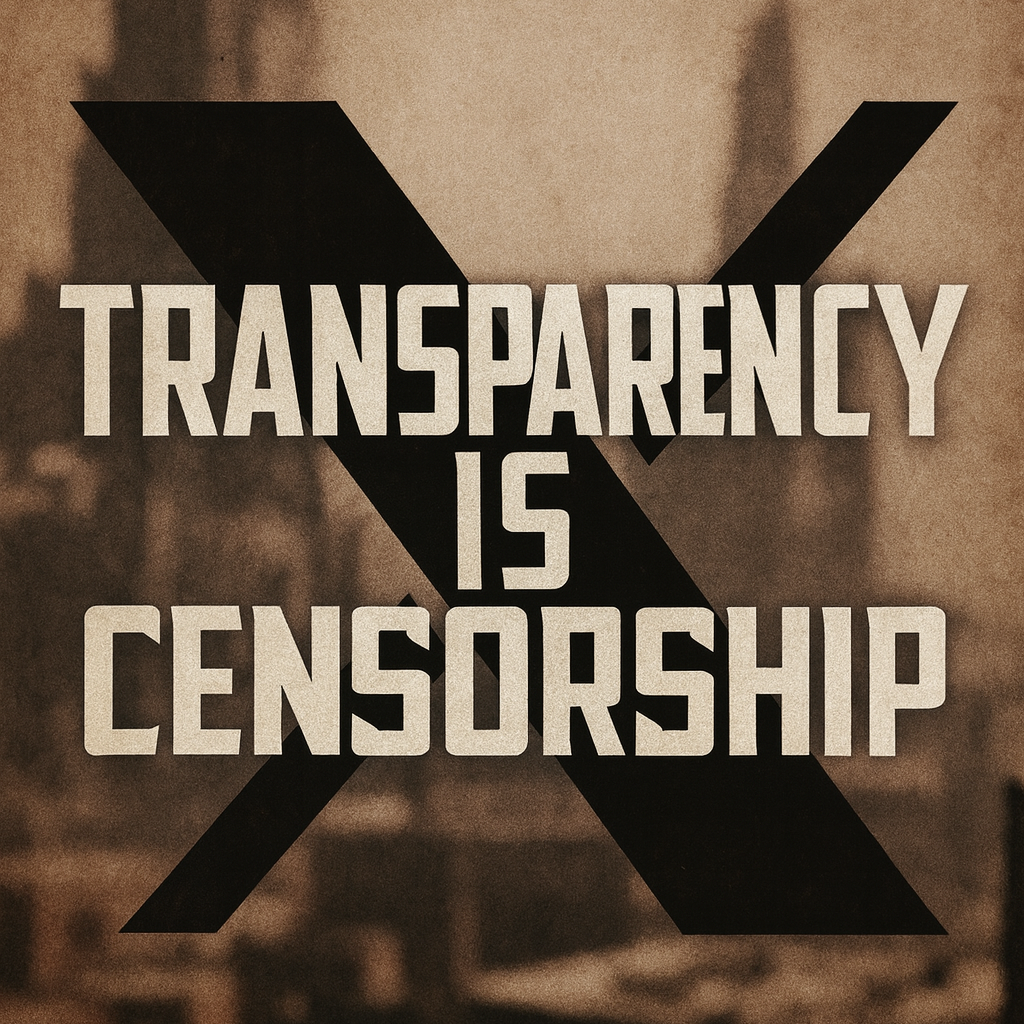

Transparency is Censorship

In my newsletter from just before Thanksgiving, I wrote about the little scandal on X in which a whole lot of MAGA folks suddenly learned that many of their favorite paidcheck influencers were not what they seemed. MAGAMom1776 was actually in Nigeria! BasedChad with the eagle avi was a man in India arbitraging the rev share program Elon had thrown together: Spend a few bucks a month on a bluecheck, pump out AI slop, LARP as an irate patriot, and profit.

There were plenty of things about the Twitter ancien régime verification system that annoyed users, but it did largely involve actual verification. Early in the COVID pandemic, when loud idiots were insisting the virus wasn’t real, Twitter awarded blue checks to select physicians as an indicator of credibility, aiming to signal to users that they were credentialed communicators and were who they claimed to be. That kind signal was stripped when Elon refashioned the feature and sold it as a product with preferential access. His gesture was intended to gratify populist rage and own the libs, which is fine—also to make some money—but the X bluecheck was still marketed as verification. Yet as the BasedChad debacle showed, it wasn’t exactly that.

European regulators consider calling something “verification” that doesn’t verify anything a consumer deception problem. So it wasn’t particularly surprising to see the European Commission nail X with a €120 million fine under the Digital Services Act last week. The Commission’s public explanation of the 3 components of the fine was straightforward: X’s blue checkmark’s design is deceptive because anyone can pay for “verified” status without meaningful verification; its ad repository isn’t transparent/usable; and it failed to provide eligible researchers access to public data. It had sent X a preliminary finding suggesting it needed to fix these things back in July 2024.

In other words: the platform broke rules it’s legally required to follow to operate in the European market—rules having nothing to do with speech.

Naturally, Elon Musk called it censorship.

Data access is censorship

Since 2018, there’s been a sustained effort to redefine anything that moderately inconveniences a right-wing populist as “censorship”. Labeling a tweet is censorship. Fact-checking is censorship. Speech Jim Jordan doesn’t like is censorship. The term has proven to be a very effective thought-terminating cliché, so the ref-workers keep applying it ever more expansively.

The DSA is an obvious target because it does have content rules; as I’ve said for years, I don’t love all of them. But in this case X was actioned under the transparency and data access obligations—some aspects of which Old Twitter had done voluntarily for years. More importantly, the Commission also went out of its way to say the DSA doesn’t require platforms to verify users…it just prohibits falsely claiming verification when none took place.

Which creates a problem for the “everything is censorship” crowd: how do you remain the aggrieved victim when the thing being enforced isn’t “take down that viewpoint,” but “stop misleading users” and “be more transparent”?

Answer: you drag transparency into the censorship frame.

And that’s how the Elon stans and Twitter Files hoaxers have responded to the EU fine—by claiming that data access is part of a “censorship-by-proxy” plot. Researchers are all secretly doing the bidding of some deep state to target Trump supporters and aligned "civilizational allies" in Europe, you see.

The OG Twitter Files theory of mass censorship has yet to be supported by any actual evidence, and the conspiracy theory keeps collapsing in court. But facts don’t matter; the stans and hoaxers aren’t actually familiar with the DSA in most cases, either. They just repeat “Digital Censorship Act” to set the frame, while the people who actually know the policies get bogged down explaining the details. The goal is simply to make transparency seem suspicious. They want the Commission not to enforce the law. Alternately, they want to render it moot: they want it to be clear that if a researcher considers asking for data to study political behavior around an election, they’ll be smeared as part of a “censorship cartel”.

The thing is, X users increasingly are realizing manipulators are prevalent in the arena. Last week, a research report from a team connected to Rutgers University was widely shared by MAGA influencers. It alleged that engagement on Groyper Nick Fuentes’ posts had components of what some platform integrity teams used to call “coordinated inauthentic behavior” (CIB): accounts that seemed like they might come from clickfarms, inauthentic amplification, retweet timings indicative of raids, etc. The report made some inferences that I think are hard to nail down without platform-side data, but overall it made a case that Fuentes is less popular than he appears. It went viral—because of ongoing right-wing political infighting: if the extremist Groypers are less popular than they seem, that’s good for our brand. Suddenly people who’d screamed about how disinformation research was all a scam were talking about retweet rates.

Analyzing anomalous coordinated behavior was something Twitter’s platform integrity team, and my team at Stanford Internet Observatory, used to do—regardless of the political or national origins involved—before it got recast as “censorship” and gutted when the ref-workers convinced Elon that basic trust-and-safety work was ideological repression.

Where things are headed?

One reason why the fake bluecheck influencers or amplifier bot networks exist is for political persuasion. The fake influencers want to develop sustained parasocial relationships. The bots are used to create the impression that large numbers of people are boosting a certain thing. Often they’re primarily preaching to their side of the aisle—performing an existing identity, reinforcing it, and rallying the like-minded rather than attempting to persuade or move people. It’s always been labor-intensive and low-fidelity; in fact, skeptics like to say that none of it matters anyway because people are practically unpersuadable.

But that may not be true for long. Two papers that just came out (in Nature and Science) found that short conversations with AI agents measurably shifted political views across ideologies. Chatbots advocating for a candidate changed minds, especially when they leaned on factual, evidence-heavy arguments. Maybe we’re headed from “persuasion is hard” to “persuasion may be less hard under conditions LLMs are uniquely good at.” I’ll dig into the details in my next newsletter—Lawfare will be doing a podcast on the topic! For now, I want to highlight the collision with the transparency fight: LLMs made manipulation easier; bot detection got harder. If conversational AI is also effective at political persuasion, it is in the public interest to be able to study how and why those systems work, both in chat settings and on social media. All of which the “transparency is censorship” crowd is trying to foreclose.

The efforts to twist a fine into tyranny whipsaw between slippery-slope melodrama and ridiculous excuse-making: “The European Commission wants to decide who gets bluechecks!” What? “Meta’s verification system works the same way!” Not really. There’s also outright hysteria: Professor Michael Shellenberger is going to Europe to explain why the fine is a violation of the NATO charter.

There is plenty of stuff to complain about within the details of European tech regulations, but let’s be realistic about what happened here: A private company wants access to a market while rejecting the rules that come with it. So it’s making a power play—because the owner believes his friends in the Administration will have his back.

Since the next decade is going to be shaped by persuasive conversational AI and platform distribution ecosystems, the public deserves visibility into both. Transparency is key. Not because oversight is inherently virtuous—but because the alternative is unaccountable private power deciding what’s credible or influential with no outside input whatsoever.

Other recent work you might like:

I interviewed Jimmy Wales for the Lawfare podcast! On Wikipedia, Grokipedia, source wars, Ed Martin sending silly letters, and building institutional trust.

I joined the amazing hosts of Trust Me — a podcast about cults by two women with firsthand experience — to talk influencers, gurus, and how social media disrupted the market for cult leaders.